The Border Beans: How Cocoa’s Price Boom Fueled a Smuggling Boom in West Africa

When the rains ended in late 2023 and the cocoa harvest began, few could imagine that this would become one of the most distorted marketing seasons in modern West African history. The global price of cocoa was soaring — reaching levels unseen since the 1970s — yet in the forest villages of Western Ghana and Eastern Côte d’Ivoire, many farmers saw little of that windfall.

Trucks rumbled at night through dirt tracks that wound toward the borders, carrying beans by the tonne. Motorbikes joined the procession, each loaded with jute sacks. Farmers called it “going to market.” Officials called it smuggling. But behind the semantics lay an old economic truth: when the price is wrong, goods move until it is right.

Between mid-2023 and early 2024, world cocoa futures more than doubled — from about $2,400 to above $5,500 per tonne, and by end-2024 they tested above $12,000. The cause was a deep structural deficit: poor weather, disease, and aging trees across West Africa had curtailed supply even as demand held firm.

But in Ghana, where the Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) fixes the farm-gate price twice yearly, the domestic rate barely changed. The Producer Price Review Committee (PPRC) met too late to capture the surge. By the time adjustments were announced, the world price had already leapt far ahead.

Across the frontier, however, the dynamics were different. Côte d’Ivoire’s partly liberalized system allowed private exporters and cooperatives to raise bids to secure beans. In Togo and Guinea, freer local markets responded instantly to international trends. The result was a glaring price gap: Ghanaian farmers could earn 20–40 % more by taking their cocoa across the border.

By early 2024, smuggling had become systemic. COCOBOD estimated that roughly 160,000 tonnes — about one-third of Ghana’s total crop — had left the country through informal channels. In the western regions of Bia, Juaboso, and Sefwi-Wiawso, buyers’ depots were half empty. “They come with cash, no paperwork, no deductions,” one cooperative leader said. “We wait weeks for our payment.”

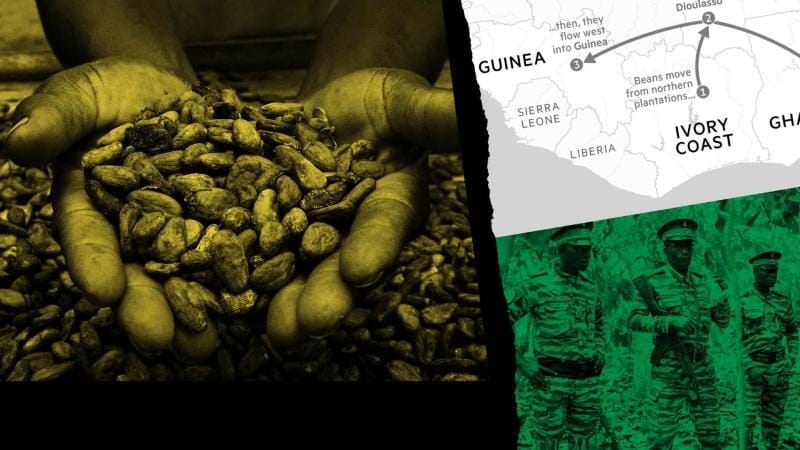

Côte d’Ivoire, meanwhile, was losing beans of its own — this time westward. Trucks bound for Guinea and Liberia carried thousands of tonnes as traders chased higher margins. In early 2024, Ivorian soldiers seized over a thousand tonnes of cocoa on these routes and suspended several officers for collusion. Industry sources later estimated total leakage near 50,000–75,000 tonnes.

The contrasting experiences of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire stemmed from their institutions. Ghana’s marketing system is fully centralized: all exports pass through COCOBOD, which guarantees farmers a fixed price and pre-finances purchases with syndicated loans. Côte d’Ivoire operates a hybrid model: the CCC (Conseil du Café-Cacao) sets a minimum price, but private exporters compete for beans.

When global prices surged, Ghana’s rigidity became its weakness; Côte d’Ivoire’s partial flexibility became its advantage. Ghanaian farmers faced a locked price. Ivorian buyers could offer small premiums, or at least pay faster. A market that was meant to protect producers instead trapped them, while a freer market next door became a magnet for their beans.

Smuggling thus became an unofficial mechanism of price equalization between the two systems — a cross-border feedback loop correcting what policy had mis-priced.

Exporters in both countries were forced to roll over part of their contracted volumes into the next season. Ghana reportedly delayed shipments of more than 150,000 tonnes, while Ivorian exporters postponed another 100,000 tonnes. At the ports of Tema, Takoradi, and San Pedro, warehouses stood half-empty, and traders spoke of “buying air” — contracts with no beans behind them.

Ship captains complained of waiting weeks for loading orders that never came, while European grinders warned of delivery delays. The visible scarcity at the ports contrasted sharply with the actual size of the harvest. Much of the cocoa existed — it simply wasn’t available through official channels.

Contrary to popular imagination, cocoa smuggling is not chaotic. It is organized, routine, and astonishingly efficient. Networks of pisteurs collect beans from farms and pay in cash, often in CFA francs. The beans are re-bagged, trucked at night to remote border points, or ferried across rivers in canoes. Along the way, small “tolls” are paid to drivers, middlemen, and sometimes local officials.

The beans then re-enter the formal chain under a different label — often sold as “Ivorian origin,” blending seamlessly into the export system. Some eventually find their way to European warehouses, their true provenance erased. It is a trade not hidden from the state but co-existing with it — a shadow supply chain moving parallel to the official one.

The tragedy of the 2023–2024 boom was that a system built to protect farmers from market volatility ended up denying them its rewards. Fixed farm-gate prices work well in stable markets, but when world prices explode, rigidity becomes distortion.

Farmers followed global prices on their phones — they saw futures hit records but watched local buyers pay almost the same as the year before. That dissonance bred frustration and flight. For many, the border was not a crime scene but a balancing mechanism.

The government, meanwhile, paid the price. Lower official arrivals meant smaller export earnings, while debt service on pre-financing loans mounted. Ghana’s cocoa receipts fell short of projections, forcing COCOBOD to tap reserves and delay payments. Côte d’Ivoire faced similar gaps on the western frontiers.

By October 2025, both governments moved decisively.

Côte d’Ivoire lifted its farm-gate price to a record 2,800 CFA/kg.

Ghana raised its producer price to 58,000 cedis per tonne, or roughly 3,625 cedis per 64-kg bag — a twelve-percent increase.

For the first time in years, the two systems converged. The arbitrage window narrowed; the border grew quieter. Early data suggest that smuggling volumes could fall by half this season — Ghana to 70,000–110,000 tonnes, Côte d’Ivoire to 30,000–60,000 tonnes — potentially restoring 50,000–90,000 tonnes of Ghanaian cocoa to official ports.

Parity, however, is fragile. It must survive currency swings, transport inflation, and the next rally in world prices. Should futures climb beyond $7,000 without a corresponding domestic adjustment, the back roads will reopen overnight.

Smuggling during 2023–2024 did more than deprive governments of revenue; it confused the world market itself.

ICE certified stocks — the inventories of exchange-deliverable cocoa held in European and U.S. warehouses — fell to multi-decade lows during the rally. Traders and analysts read this as evidence of a severe physical shortage. But part of that “shortage” was statistical illusion: tens of thousands of tonnes of Ghanaian cocoa were being sold unofficially through Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and Togo, bypassing official export records.

Shipments that left Abidjan or Conakry labeled as “Ivorian” or “Guinean” origin were, in truth, Ghanaian beans. This re-labeling distorted trade data, making Ghana’s output appear to collapse while Côte d’Ivoire’s exports seemed resilient. Importers saw tightening supply; speculators saw scarcity; prices rose further — reinforcing the very incentives that caused the smuggling.

In effect, the market began to trade on shadows. Futures prices reflected not the balance of supply and demand, but the opacity of the border. Analysts misread the decline in Ghana’s official arrivals as a production failure rather than a diversion. The feedback loop was perfect: higher prices encouraged more smuggling, which in turn reduced reported stocks, justifying even higher prices.

The phenomenon was self-reinforcing until policy finally caught up. Only with the 2025/26 parity hikes did the feedback begin to weaken.

If parity holds through the main crop, 2025/26 could mark a structural turning point — the first season in years when farmers have little reason to divert beans across borders. Yet lasting stability will require more than matching prices. It demands faster payments, transparent grading, and a harmonized price-review calendar between Accra and Abidjan.

Modernization is already on the table: digital payment platforms to shorten remittance times, joint monitoring of arrivals, and early-warning systems for currency gaps. These are the quiet reforms that could make smuggling economically irrational rather than morally questionable.

For the global market, fewer invisible flows mean clearer data and steadier prices. Recovering just 70,000 tonnes of officially recorded Ghanaian exports could ease the deficit narrative that gripped futures traders in 2024.

But West Africa’s experience also offers a universal lesson: when policy lags the market, the market finds its own routes. In cocoa, those routes run through forests and rivers — invisible on a map but vivid in every price chart that spikes higher than it should.

For generations, the Ghana–Côte d’Ivoire frontier has been porous, more cultural than cartographic. Families farm on one side and sell on the other; traders speak both Twi and French. The cocoa tree knows no passport.

When governments align their prices, the border quiets. When they don’t, it hums again with nocturnal traffic. The record farm-gate hikes of 2025 have drawn the line straight, for now. But the next rally, the next drought, or the next delay in payment could bend it once more.

The lesson, as old as the trade itself, is simple:

When farmers are paid fairly and promptly, they stay home. When they’re not, the road to the border is always open.